The Legend of the Levitating Stone

Shona Adhikari

Throughout the world are these marvels of nature, quite often not recorded. Our Shona has written about this amazing feature. As teenagers I remember at parties we learned how to use the fingers of five or six persons to lift persons into the air. It was a party game that we enjoyed playing. In this article by Shona the divine strength appears from the uttering of the Saint’s name. Read on…

Tucked away somewhere in the back of my mind was the memory of having seen a large stone being lifted by a group of people with one finger. I must have been all of five years of age at the time, and living in Poona, where my father an Army officer was posted. I remember being amazed and wanting to try it out myself - I was of course told that I was too small.

Years later when visiting Pune (Poona had now become Pune), I had the opportunity of visiting the site of the levitating stone. I was told that this famous stone lay in the courtyard of the Durgah of Hazrat Peer Kamarali - a popular place of pilgrimage for people of all faiths.

The Durgah is situated on the Satara road, and can be reached from Pune by road within half an hour. Built of white marble, it was constructed by Suresh Warkar, a devotee of Kamarali Durvesh. The exact age of the Durgah was not readily available, but someone volunteered the information that it corresponded to 632 Hijra on the Muslim calendar. Warkar is said to have spent 35 lakhs to build the tomb, as all the marble had to be specially transported from Makrana. The Durgah has a large dome and minarets in the four corners. Texts from the Koran inlaid in black marble, form an intricate border above the arches. The tomb has a green and white painted boundary wall, as well as places for people to rest.

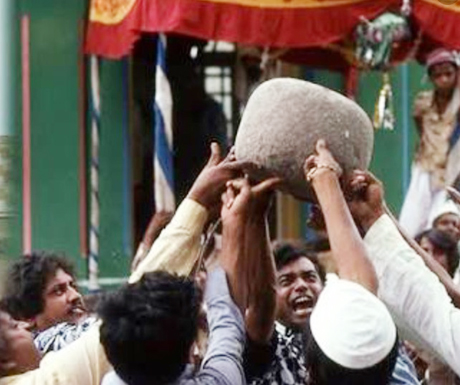

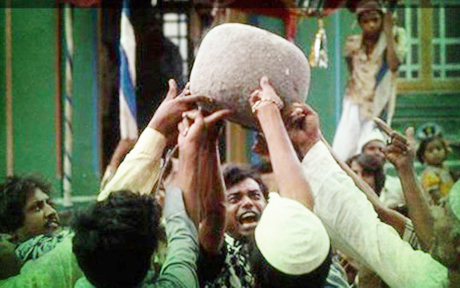

The famous stone lay in the courtyard, looking rather innocuous on a patch of gravel - waiting as it were to be lifted up. The stone which is said to weigh 90 kg, can be made to rise on the index fingers of a group of nine or eleven persons ¬who must chant the saint's name all the while. As soon as one of them stops chanting 'Hajee Kamarali Durvesh', the stone falls down.

There are many who wait just outside the gate and for a fee, are willing to make up a group to demonstrate what seems to be a miracle. Needless to say, I simply had to see this, and if possible photograph this amazing feat. A group was created within minutes, and as they began chanting the saint's name the stone was slowly lifted up, only to come tumbling down when they ran out of breath. It is said that all those who lift up the stone should count themselves as specially blessed by the saint.

The sad part was that I as a woman was not allowed to try out this special feat, and in fact females were not even allowed inside the tomb. A number of women were seen waiting outside the entrance and sitting on the steps outside, on the day that I visited the Durgah. It was a Thursday which is said to be the most important day for visits. The Saint's Urs is celebrated in early May, when a large number of people come from far and near to visit the Durgah.

There is an interesting story about the powers of the saint. Whenever someone is bitten by a snake, all they have to do to be cured is to come to the Durgah, and put a drop of oil on the bite, from the oil lamp that remains lit all the time. While this appears to be pure superstition, the villagers in the area, swear by this cure.

During my visit I also met a film director from Mumbai, who comes to the Durgah regularly. His visit at that time was to offer thanks to the saint for making his last film a success. On his earlier visit he had tied a red string on the jali next to the Saint's grave, and when I met him he had come to untie the string, since the favour had been granted. The director's faith in Kamarali was the result of a visit with a friend, at a time when business was particularly bad. Depressed at having lost all his money, he agreed to come to the Durgah after much persuasion. Having tied a string on the jali, without really expecting anything, he was pleasantly surprised when on his return to Mumbai, he immediately landed a lucrative contract. From then on he visits the Durgah regularly.

One of the women sitting at the entrance to the Durgah, informed me that after a visit to Kamarali, her daughter who had been lost, was restored to her. A resident of Pune, she now visits the Durgah at least once a month to offer thanks. There are many who visit the Durgah before they start any new business, get their children married, and even bring the sick hoping for a cure. While faith is a wonderful thing, and many seemingly impossible things can result from it - much of it is often the result of personal effort.

However, what of the levitating stone? Is there a simple explanation for this phenomenon? To me it seems rather like the saying 'faith can move mountains'. And a demonstration of this faith is there for all to witness over and over again, everyday. All one has to do is chant the Saint's name, and seemingly even 90 kgs can be lifted on just nine or eleven fingers - if that is not a miracle, then what is?

- - -